A Mother’s Justice – Rural leadership profile: Nancy Van Milligen

The Chicago suburb of Skokie, Illinois, was home, for many years, to the world’s largest known population of Nazi concentration camp survivors outside Israel. There’s a Hollywood movie about Skokie’s community’s struggle when a neo-Nazi group planned a march there in 1977, and that struggle led to the establishment of the Illinois Holocaust Museum in 1981. Still, national awareness of Skokie’s importance to Holocaust history isn’t high.

But for Nancy Van Milligen, today President and CEO of the Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque (CFGD), the remembrance of Skokie’s survivor community is seldom far from her thoughts. At the turn of the 1980s, she was living there with her husband, who was Skokie’s Assistant Village Manager. As she retells it, “he was charged with erecting a monument on the village green in honor of the survivors. At the unveiling, we’re in a room with four hundred people who have lived through the concentration camps. I was so young. Nothing bad had ever really happened to me. And here were these beautiful people, resilient people. It was unbelievable. It changed my life.”

Once she recovered from the shock of “the realization of evil and true evil,” she says, the change that came over her “was the understanding of the importance of ethical leadership.”

Something else happened for Van Milligen around the same time: she and her husband started a family. The firstborn of their five children arrived in 1980; since then, they’ve fostered two dozen more, including a pair even today, when the Van Milligens are not just foster parents but also grandparents. “We have never not had children in our house,” she says.

It isn’t hard to see the connection between her experience of the Skokie Holocaust memorial and her lifelong taking-in of children. This is someone with instincts that are more than maternal. Van Milligen is impelled not only to gather, protect, and provide for the neglected and the victimized, but also to honor them with public inclusion and welcome—to center them in the community, by the community. Right on the village green.

She says it best with the very first sentence of her bio: “In the public sphere, a mother’s love becomes social justice.”

Justice, ethics, love, inclusion—these are all elemental human ideals. But there is a very practical element at work here. “Iowa has ninety-nine counties, and ninety-one of them have lost population every year over the last seven to ten years,” Van Milligen says. “Our biggest need is people. We need skilled workers, we need immigrants. If we aren’t welcoming to immigrants, we will not thrive.”

In 2012, IBM opened a facility in Dubuque and hired a diverse 1,300-person workforce. Some of its nonwhite employees were made to feel unwelcome in town. IBM came to community leaders, including CFGD, with an urgent and pointed demand: “If you don’t fix that, we can’t stay.”

Van Milligen’s fix stayed true to an axiom of hers that has guided her for years in thinking about rural and small-town prosperity, which has since become a watchword of the New Profit RST Action Summit: “We don’t need stronger organizations. We need stronger communities.” Outsourcing IBM’s problem by starting a new, independent nonprofit “just felt to me like hiring some person [and saying], ‘okay, fix racism.’” Instead, CFGD fostered community by creating a peer-learning network called Inclusive Dubuque that engages people collaboratively to address bias in the community. The network has not only succeeded, it has expanded significantly. Inclusive Dubuque is now a locus for diversity and equity programs and workshops throughout CFGD’s community; and, just as it was conceived in response to a specific, urgent need, it remains able to respond to exigencies as they arise. After the murder of George Floyd convulsed the country, Inclusive Dubuque introduced racial healing workshops.

Van Milligen cites a Knight Foundation study called Soul of the Community. Over the course of three years from 2007-10, the study engaged Gallup to conduct a poll that sought “to determine the factors that attach residents to their communities and the role of community attachment in an area’s economic growth and well-being,” in the study’s words.

“You would think it’d be low taxes, good jobs,” Van Milligen says. But the findings were surprising. “Instead, the three things were: natural beauty; social offerings—the art museum and the golf clubs and the bowling alleys—and the third one was being welcoming to everyone.”

In other words, the data are in line with her community’s practical needs—fostering diversity as a matter of survival—and with Van Milligen’s inclusive, come-one-and-all instinct.

That instinct is complemented by another. Van Milligen calls it “the itch that I have. I’m always trying to figure out how to solve the problem, to see paths to making it better,” she says. Sometimes the itch “drives people crazy,” she says. But she’s never willing to stop scratching at it even when the rest of the room has declared the path clear enough to see.

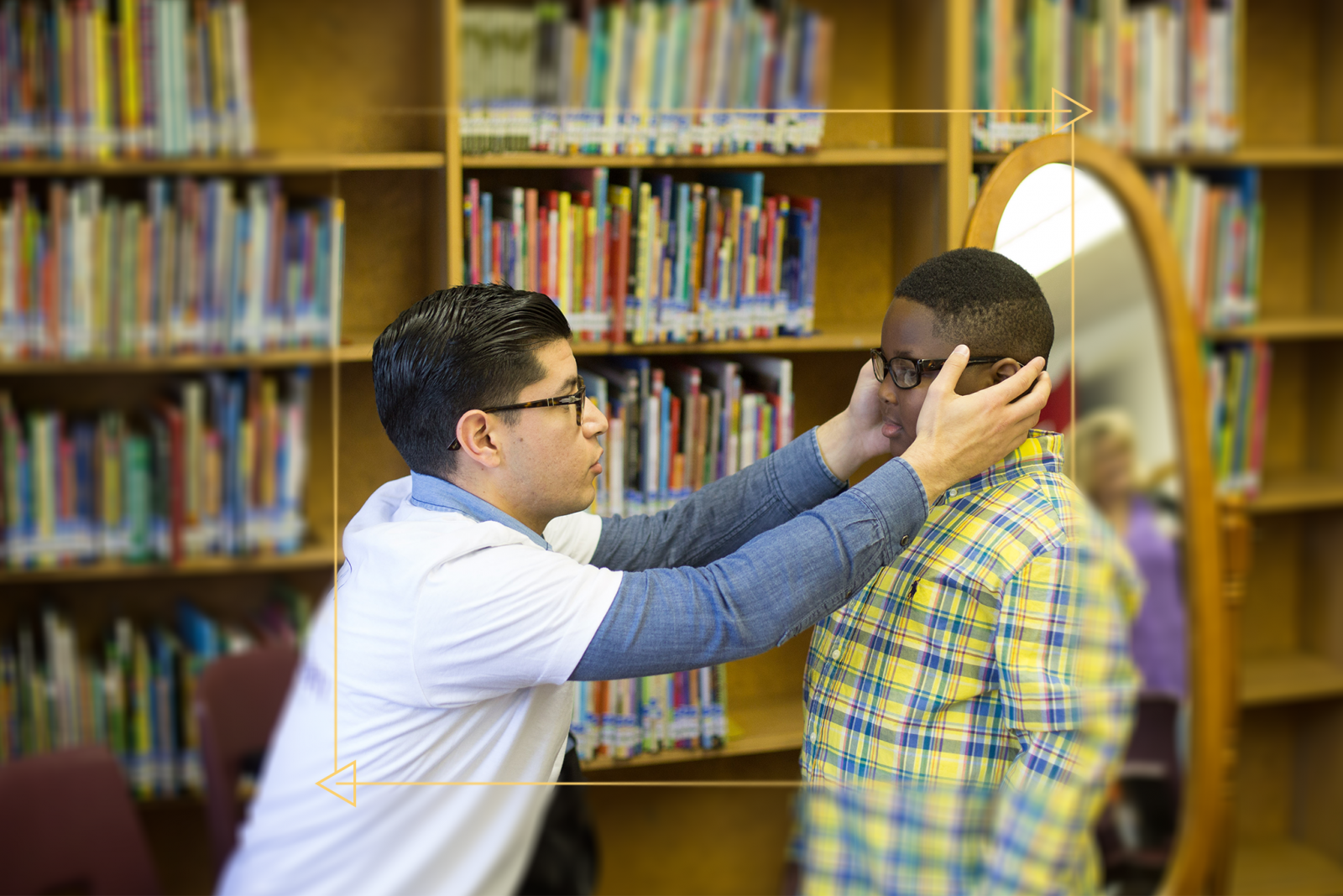

Here’s a vision-centered example. A few years ago, a CFGD initiative to provide disadvantaged Dubuque kids with eyeglasses attracted community members who offered to drive kids to eye tests and fittings with local optometrists. “I love volunteers and I use them all the time when I can,” Van Milligen says, “but I want all kids to have glasses. Volunteers driving kids to the doctor isn’t going to make that happen”—and there were Medicare obstacles with optometrists, too.

At a conference Van Milligen had attended, she met the founder of a California nonprofit who ran Vision to Learn: a sort of bookmobile, but instead of books, the bus was full of eyeglasses, and instead of a librarian, it was staffed by a volunteer optometrist.

“So I called them up and said, ‘Hey, we’d like to try this.’” The bus drove all the way from California to Dubuque, which became Vision to Learn’s first foray out of state. Instead of lots of short drives to help a few kids, Van Milligen initiated one long one to help hundreds. And the drive, so to speak, continued after the bus went back to California. Van Milligen got a donor to buy the Northeast Iowa region its own bus, which now serves not only the entire area but much of the state and beyond. The program has fitted more than 5,000 kids with glasses, and each kid gets to take two pairs. That’s a crucial improvement that very few people would be able to identify, and Van Milligen, rooted where a mother’s love meets social justice, is one of them: In foster programs, kids only get one pair every two years.

President and CEO of Community Foundation of Greater Dubuque